Pittsburgh MMA – The birthplace of Modern Mixed Martial Arts

By the late 1970s the Pittsburgh mixed martial arts scene was approaching a crescendo. The journey had been a long gradual process that produced some of the 20th century’s most legendary fighters, boxers, wrestlers, and martial artists. Viola explains, “To understand where we were going, you have to appreciate where we came from. Pittsburgh was the perfect place to attempt a new sport, and the only way to set the stage is to grasp all its traditions and history. Our idea was the product of a movement that started nearly a century ago. It was a time and place that just can’t be replicated.”

The Steel City

“As iron sharpens iron, so one man sharpens another.”

-Proverbs 20:17

With boxing and wrestling already commonplace, the first martial art to make an impact in Western Pennsylvania was Kosedido-ryu Jiu-Jitsu in the 1920s. Dewey Deavers would establish The Allegheny County Budo Kai in 1927, a dojo dedicated to teaching that style; a combination of strikes, kicks, joint locks, take downs, chokes and submissions (a skill set learned by training with touring Japanese jiu-jitsu and judo experts circa 1910). Deavers’ methods were truly one of the earliest examples of mixed martial arts in the United States; homegrown in Pittsburgh. “There were no Illegal techniques,” explains Sensei Joseph Hedderman (a student of Deavers since 1950 and now the highest ranking instructor of the system). “The dojo was founded on the principles of self-defense training above all else. Classes back then could be rough. Students regularly practiced ‘no rules’ ground fighting and learned resuscitation techniques by first being choked unconscious and then revived.” Viola adds, “Everyone is familiar with Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, but Pittsburgh had its own ‘no-holds-barred’ jiu-jitsu too. It’s one of the greatest kept secrets in marital arts.”

During the great depression, Deavers trained alongside a contingency of Gung-Fu practitioners while working at a Chinese restaurant in Pittsburgh’s Chinatown section. They would frequently demonstrate for the patrons, offering a rare glimpse into the psyche of martial artists during period when public displays of such guarded ancient methods were almost taboo. Today Hedderman continues to lead the Allegheny County Budo Kai, now a landmark institution, dedicated to preserving Deavers’ legacy.

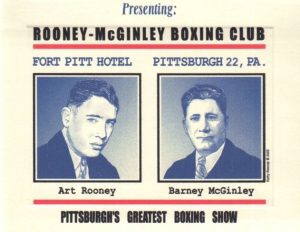

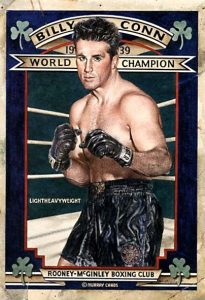

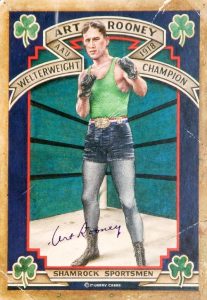

During the 1930s and 40s the famed Rooney-McGinley Boxing Club put Pittsburgh prizefighting on the map. Art Rooney, the founder of the Pittsburgh Steelers, partnered with Barney McGinley to promote gladiators on the gridiron and the canvas. John R. “Jack” McGinley Jr. [Barney’s Grandson] jokes about the Fort Pitt Hotel headquarters, “They had a desk. One drawer with football tickets, the other boxing tickets.” The gym became “the” place to train for champions like the “Pittsburgh Kid” Billy Conn.

Billy was regarded as one of the greatest pound-for-pound fighters of all time; a trifecta: handsome, athletic and charismatic. “Conn was a family friend, so much so that Art [Rooney, Sr.] even stood as Godfather for [Tim Conn] one of his kids,” says McGinley, Jr.

The public perception of boxers in the 1940s was on an entirely other level. When asked if Billy Conn was the equivalent of Ben Roethlisberger [Pittsburgh Steeler Star Quarterback] in terms of celebrity status. McGinley quipped, “No he was more like the Michael Jordan.” Conn was a beloved national hero, Hollywood celebrity, and household name. It was a testimony not only to boxing’s popularity but to the clout associated with its hierarchy. The night Billy Conn “won and lost” the heavyweight title from Joe Louis in New York, over 24,000 fans sat at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh to watch the Pirates play baseball. The umpire suspended the game so the anxious crowd could listen to the fight over the P.A. system. At that moment Pittsburgh and most of America stopped. Boxing gripped the nation.

In 1951 Barney’s son Jack McGinley Sr. promoted the first major heavyweight championship in the city’s history, a match between Jersey Joe Walcott and Ezzard Charles at Forbes Field. The bout was Ring Magazine’s “Fight of the Year,” attracting a virtual who’s who of boxing legends; Billy Conn, Fritzie Zivic, Teddy Yarosz, Primo Carnera, Joe Louis, and Rocky Marciano. Viola remembers, “My dad, [William ‘Sketes’ Viola] also sat ringside that day, rubbing elbows with the greats. McGinley Jr. recounts “The buzz was everywhere… It was like the first Superbowl.” (Jersey Joe would later fight mixed-fights with pro-wresting stars “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers and Lou Thesz.) Most historians concede that these were likely predetermined fights, a frequent way for ex-boxing champions past their prime to earn a paycheck.

Jack McGinley, Sr. says, “Television killed boxing here.” By the early 1950s fans chose to stay home and watch fights on TV instead of attending them live. Although boxing may have been Barney McGinley’s first love, the writing was on the wall. He and Rooney turned their attention to football and never looked back; a difficult decision, but ultimately the right call. Today, the Steelers franchise is a billion dollar entity while boxing never regained the glitz and glamour of its heyday. As to the future of Pittsburgh boxing, McGinley sadly admits, “Those days are over…I can’t name four [top boxers] today… I think mixed martial arts has a chance.”

Judo continued to enjoy widespread popularity through programs established by Nick Zaffuto, a young Marine who studied the art while stationed in Pearl Harbor in 1945. By the 1950s a smattering of Okinawan and Japanese arts were certainly present and gaining momentum, while lesser known styles such as Indonesian Pentjak Silat were popularized by the controversial Willy Wetzel of Beaver County in 1956. Wetzel developed a mystique with rumors of a “death match” he fought in Indonesia, and later his own death [homicide] at the hands of his son Roy. The subsequent murder trial made headlines with testimony reminiscent of a wild martial arts movie script depicting a battle with swords, knives and a pair of nunchuku. His son was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense, but the incident undoubtedly raised an aura of mystery around the Pittsburgh martial arts.

Joseph Hedderman, already versed in Jiu-jitsu, studied Shotokan karate under Victor Lemire while in the US Army (stationed in Ft. Leonard Wood Missouri in 1957). In 1959, Hedderman was honorably discharged from the service and incorporated Shotokan into his curriculum, becoming the first person to openly teach karate in Pittsburgh. In 1959 Sensei Harry G. Smith, a direct student of Tatsuo Shimabukuro (Founder of Isshinryu) opened one of the first karate dojos in Eastern Pennsylvania, which led to a sister school in Pittsburgh in 1962. Throughout the early 1960s, martial arts became readily accessible to thousands of willing students and schools began to thrive. In 1961, Teruyuki Okazaki began instructing Shotokan Karate in Philadelphia, and his teachings quickly spread to Western Pennsylvania through a number of satellite dojos. Pittsburghers would reap the benefit of some of the earliest and most diverse martial arts in America.

The 1960s were also abuzz with various forms of submission wrestling, catch wrestling and professional wrestling, shaping the attitude of Pittsburgh fight fans. Pittsburgh pro-wrestling icon Bruno Sammartino was the longest running champion in WWF (now WWE) history, a fact that blue-collar hardnosed Pittsburghers took pride in. He was the quintessential tough guy; big, strong, and fearless. The beloved wrestler had legions of loyal fans from around the world, not just Western Pennsylvania.

“Old School” karate tournaments were soon in the limelight; many times resulting in bare-fisted knockouts. The sparring of yesteryear was more a test of toughness than finesse. Under the direction of Harry Smith, Pittsburgh hosted its first tournament in 1963. Techniques were only deemed worthy if the force could subdue the opponent with a single blow; they didn’t disappoint.

In 1970, William Duessel and Chuck Wallace continued the city’s Isshinryu tradition, opening what would become the era’s largest dojo in Pittsburgh with over 500 students. “Duessel and Wallace used to march into my tournament with easily 100 of their top students to compete. They had an incredible stable back in those days,” says Sensei Bill Viola. Frank Caliguri and Bill Viola, the “C” & “V” in CV Productions, had established thriving karate dojos by this point; Viola’s Allegheny Shotokan in 1969 and Caliguri’s Academy of Martial Arts in 1970.

Korean imports such as Tae Kwon Do first surfaced in Pittsburgh during the early 1970s with the emergence of Masters Augustine K. Lee and Shin Duk Kang. Tae Kwon Do electrified crowds with flashy kicks and dynamic breaking displays. Once again, the public was intrigued. Dr. Rick Lengyel was an early instructor at Kang’s Black Belt Academy, a renaissance man who added Tae Kwon Do to a resume that already included karate, judo and boxing. His diverse skill set led to Pittsburgh’s first “non-classical” karate studio, The Institute of Progressive Martial Arts in 1975. Lengyel recalls, “There were no uniforms, you could wear your shoes, and we focused more on footwork; combining boxing with karate.” The movement towards “free thinking” was amidst a major transition period for American martial arts, as the PKA (Professional Karate Association) spearheaded mainstream kickboxing (aka full-contact karate). Pittsburgh was a hotbed of contenders including one of the most prolific fighters of the time, World Champion Jacquet Bazemore.

Jacquet Bazemore with Muhammad Ali

Pittsburgh was home to champions in every facet of the fight game. With such passion, blind loyalty and conflicting egos among boxing, wrestling and martial arts enthusiasts, the fans craved something more by the late 1970s. Years later in 1993, the UFC asked America who is the “ultimate fighter?” Mixed martial arts would answer the question, but the birth of this radical new sport was actually right around the corner in 1979.