How Hollywood made MMA inevitable

“Reality leaves a lot to the imagination.” – John Lennon

In the early 1980s, martial arts were still very much a part of the American consciousness, but moving in a more conservative direction. In 1984, John G. Avildsen, the directorial genius behind Rocky, put a new spin on the classic underdog story in the form of The Karate Kid. The “PG” drama was an instant blockbuster, especially among children, and made Mr. Miyagi (academy award nominee Pat Morita) a household name. While the “wax on wax off” era popularized a “family” karate atmosphere, it did little to advance mixed martial arts. The movie ushered in a fresh base of young fans and practitioners as kids flooded karate studios.

A wave of “McDojos” emerged, questionable schools with even more questionable ethics that blatantly rewarded mediocrity. “They were practically belt mills.” Bill Viola remembers. “Suddenly schools were opening on every corner. They were passing black belts out to kids like it was candy. These so-called masters were a joke. The practice gave people the wrong impression of true martial arts.”

As revered as karate was in the 1970s, martial arts struggled to define its identity during the mid 1980s. A watered-down version of marital arts inspired spoofs like The Last Dragon (aka Bruce Leroy) and off-the-wall cartoons led by the animated children’s hit The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Ninjas, a once feared assassins famous for guerilla warfare, were reduced to nothing more than a stereotype; sword-toting rouged warriors dressed in black pajamas, throwing stars and flying through the air using “mind control” tactics on unsuspecting victims. Suddenly, “American” Ninjutsu schools were popping up to cash in on the art of stealth. Martial arts were exploited from every angle to make a quick buck and frankly losing some credibility in the eyes of inexperienced fight fans.

Of course there wasn’t any shortage of “tough guys” in the entertainment industry as action heroes Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger ruled the silver screen. They incorporated hand-to-hand combat through memorable characters like Rambo and Conan. Meanwhile, Chuck Norris joined the ranks through a series of military based hits that included the Missing in Action series. Martial arts were present and enhanced the films but weren’t as pure as they once had been.

The Rocky Franchise continued to flourish with the release of Rocky IV in 1985 (the highest grossing sports film at the time raking in 300 million dollars worldwide). Its success proved that boxing was still very much cemented within American culture. Viola jokes, “Who can forget those Ivan Drago quotes, ‘I must break you.’”

By 1987 a curious arcade game shifted the attention back to combined martial arts combat via the wildly popular Street Fighter. The billion dollar game franchise featured a fantasy, a no-holds-barred competition where players could live out a virtual experience. UFC 1 competitor Art Jimmerson was quoted as saying, “They [UFC] needed a boxer [and] I was ranked in the top ten light-heavyweights in boxing. ‘Street Fighter’ was one of the biggest video games out at the time, and my kids loved it.” Their enthusiasm encouraged Jimmerson to compete in the UFC. Jimmerson was basically a sacrificial lamb in that first UFC competition, truly out of his element. Wikipedia actually lists the method of submission as “terror” because he actually tapped out prior to Royce Gracie cinching in his choke attempt. It was a symbolic match that Rorion had orchestrated to target “American” boxing, a fight that purposely illustrated the prowess of Gracie JiuJitsu.

The “style vs style” fighting concept was further sensationalized in the 1988 motion picture, Bloodsport, a big screen forerunner to modern MMA competition. The cult classic launched the career of action-star Jean Claude Van Damme; dubbed the “Muscles from Brussels,” famous for his chiseled physique, splits and kicks.

The story line was supposedly based on “true life events” of Frank Dux, a covert operative who allegedly competed in secret no-holds-barred competitions in the mid 1970s. The film’s clever marketing campaign raised some eyebrows and gave people the perception that a mystical all-encompassing martial artist existed in real life.

Regardless of the plot’s creditability and “awesomely” bad acting, Hollywood spun it, and America bought it big-time. The movie’s “Kumite” was an epic invitation to a mythical underground tournament, a collective of the world’s most dangerous men. A new generation of fans connected with the “ass kicking” nature of the film and a fictitious champion of champions among all the martial arts.

The following year Best of the Best was released, continuing the martial arts tournament theme but emphasizing “sport” competition. The plot followed the journey of an American team faced with seemingly insurmountable opponents. The movie is said to have inspired future UFC champion Chuck Liddell, naming it his favorite martial arts film in his book Iceman, My Fighting Life.

Simultaneously, conventional karate champions began to lose their luster while pro wrestling’s stock seemed to soar. Hulk Hogan poised himself to become one of most recognizable names in sports history, personally leading a charge that would eventually set new pay-per-view records.

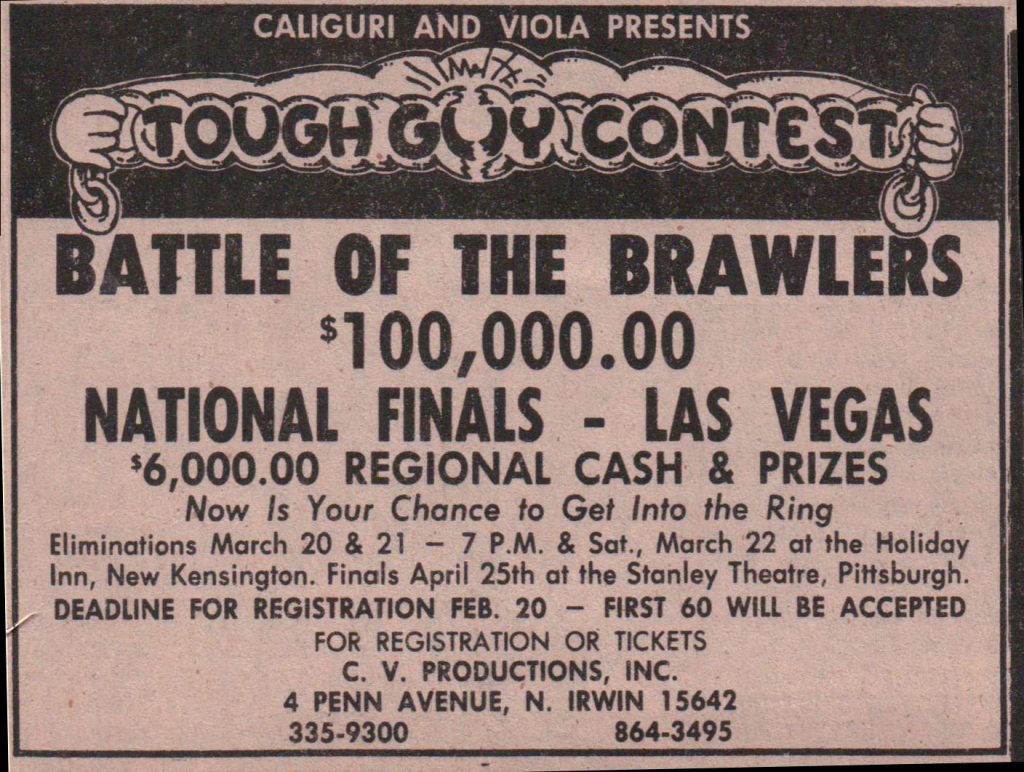

In 1989, the “Hulkster” would star in the feature film No Holds Barred portraying the WWF’s [World Wrestling Federation] version of a modern gladiator. It was the company’s first attempt at capturing a market share of the action film genre. The movie trailer rang a very familiar bell promoting an anything-goes competition conspicuously named, “Battle of the Tough Guys.” Not only did they steal CV Productions’s name word-for-word, but they ripped off the entire Caliguri/Viola theme and replaced it with a cheesy “pro wrasslin” type script that paralleled MMA. Viola jokes, “The only things worse than the acting were the awful ‘80s soundtrack and outfits.”

Viola’s reaction years later was simple disgust, “Are you kidding me! When my son brought this to my attention I couldn’t believe it; I’m not a pro-wrestling fan, so I never saw the movie back then. Now that it is coming out on DVD for the first time [2012], people are talking. Two decades passed before I even heard about that hack job, but make no mistake it was an infringement of our intellectual property. By the late ‘80’s our ‘Battle of the Tough Guys’ may have faded away, but I would have never let something so obvious slide. They stole our name and concept right down to their make believe contest and $100,000 grand prize. Granted, they did a terrible job (movie critics agree) and butchered the idea, but a few years later the UFC gave audiences a live version of the movie. If Frank and I would have caught wind of this back then, we would have sued the shit out of the WWF.”

The movie’s theme may have been swiped from CV Productions, but it was clearly a few steps ahead of the UFC in some respects with its, “No Ring, No Ref, No Rules” approach. Actually, the movie does give fans a glimpse at a unique ring, an octagonal one in fact. Steel cage matches were very common in the WWF, so a combination of the two is very conceivable. I guess you could say it was something borrowed, something new [Laughs]. It was my dad’s and Frank’s brand the WWF put up on the screen; they just embellished it in typical ‘hollyweird’ fashion. Then a few years later the UFC seemed to pick up the ball and run with it—never looking back.

Of course it’s all loosely based, but it seems a bit too coincidental. The original “Battle of the Tough Guys” sparked a reality fighting craze in 1980 only to set the stage for scores of imitations, unregulated underground contests and of course Hogan’s dramatic and exaggerated movie. It would not be long before the UFC would bring the reality concept full circle. It’s a crazy sequence of events.”

In September, 1989, the television show American Gladiators debuted. The show pitted talented amateur athletes against professionals in competitions that included agility and stamina along with fighting skills. The origins of the show were reminiscent of the early days of CV Productions’ “Battle of the Brawlers” competitions. The show had its roots in Erie, Pennsylvania, hometown of Mad Dog Danny Moyak, The Lower East Side Federation, and “Apache” Dann Carr, the same Dann Carr who had nearly caused a riot at the Stanley Theatre finals.

The prototype for American Gladiators was held by Carr and fellow producer John C. Ferraro at the Erie Tech High School. Their concept was sold to MGM, who developed it into a television series. Carr may have been paying attention to the way CV Productions ran its events, and if so, he benefitted from the experience.

The show was just that, a show. Contestants and house pros (men and women alike) engaged in events that ranged from strength tests like tug-of-war to fighting on pedestals with pugil sticks and running obstacle courses while dressed in spandex and sequined outfits that suggested comic book heroes and accentuated hard bodies. The show was a lot of glam with its outlandish costumes and sets, but it served as a cultural transition for the shock-and-awe staging to follow in the UFC.

Sports in many ways are ritualized combat, and are designed to hone fighting skills. Swinging a baseball bat or tennis racket to strike a moving object teaches one to accurately swing a battle axe or mace at an antagonist’s head. Gaining yardage on a football field is analogous to advancing across a battlefield to seize territory from the enemy. In American Gladiator, the games were combative but far from the hard-core reality of the Roman Coliseum. Blood seldom dripped on the spandex. Yet, the show edged closely enough to whet the public’s appetite for less cartoon and more reality.

CV Productions brought competitive fighting full-circle from the formalized, idealized “combat-as-sport” of the Olympics and pro boxing to the “sport-as-combat” of combined fighting. However, it was an idea far ahead of its time, and consequently feared by an establishment complacent in its ruts of habit.

While American Gladiators mimicked combat, an obscure Brazilian gladiator attempted to import a more realistic version. Rorion Gracie had set up shop in California earlier in the decade and eventually reinstituted the “Gracie Challenge,” an open invitation to fight anyone in a no-holds-barred match, sometimes for big money. The challenge was made famous by his Uncle Carlos, the same man who took out aggressive newspaper advertisements in Brazil with an in-your-face campaign that read, “If you want a broken arm call Carlos Gracie.”

The Gracies would become known as the “first family” of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu and Rorion (the eldest son of Helio) made it his mission to showcase the family’s unique skills. Heilo, now the family patriarch, popularized the adaptation of judo and jiu-jitsu techniques (aka Kano-Jiu-jitsu) taught by his older brother Carlos. As he further developed the style of leverage and submissions, he deemed necessary to rebrand the art; “Gracie Jiu-Jitsu.”

Throughout the 1980s Rorion had made some headway sharing Gracie Jiu-Jitsu, but the art was still relatively isolated to a West Coast niche. Gradually, people began to take notice of the art, and in 1988 even Chuck Norris hosted a Gracie seminar for his black belts in Las Vegas.

While Rorion was building momentum, Shooto, the Japanese equivalent of “real” pro-wrestling matches established by “Tiger Mask” Satoru Sayama, arrived on American soil in the late 1980s. Mixed Martial Arts was ready to break out—again.

Viola explains, “Rorion caught a big break when Playboy Magazine (September 1989) gave Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu its first taste of real American publicity.” Interviewer Pat Jordan proclaimed Rorion Gracie the “Toughest man in the United States.” The buzz caught the attention of advertising mogul Art Davie, who had been fascinated with a no-holds-barred fighting after he heard colleagues boast about nightclub brawls promoted in Thailand.

Viola continues, “It seems Frank and I weren’t off base with the ‘Tough Guy’ imagery, it’s a reoccurring theme.” That article sparked a series of events and the chance encounters of Rorion Gracie, Art Davie and Hollywood director, John Milius. Viola adds, “They all worked out together, so it was just a matter of time before they had their ‘ultimate’ collaboration.”

In the meantime, action junkies had a very short attention span and in the early 90s’ the country became fixated on a new bad ass, Aikido aficionado Steven Seagal. As always, the line between reality and fiction was put to the test when supposedly an impromptu encounter lead to a “pissing match” so to speak between Seagal (aikido) and stuntman Gene Lebell (judo) while on the set of Out For Justice. Rumors quickly circulated that LeBell effectively choked Seagal unconscious after a challenge.

In true Hollywood fashion the alleged incident blew up and became the “talk” on the internet. Whether or not any truth lies in the story, once again it sparked a lively debate about what style of martial arts was superior. The era left a very confused and equally stubborn American audience. Everyone had an opinion of what the “best” martial art was, regardless of whether they ever trained a day in their lives. As Viola jokes, “Every couch potato seemed to be an expert.”

Not to be outdone, Rorion Gracie never lost sight of his goal to promote his family name networking his way into teaching Mel Gibson Jiu-Jitsu for the Lethal Weapon franchise (parts I and III). As Tinsel Town toyed with the notion of mixed martial arts, Rorion had already moved forward with the distribution of the Gracie in Action video series, a visceral account of Brazilian jiu-jitsu that documented his family’s conquests. Art Davie was instrumental in developing a direct mail campaign to market the videos.

Viola adds, “Long story short, after Davie began training with Gracie, the pair eventually hatched the idea of a pay-per-view tournament (martial art “style vs style”) called “War of The Worlds” and began pitching it 1992. Milius was also a student of Gracie at the time and he brought his film experience, contacts, and creditably to the table. They were getting close.”

By the Fall of 1992, the video game Mortal Kombat was released, and with it a firestorm of controversy. It was known for graphic violence and famous for “fatalities,” (finishing moves where the players could kill their opponents). The game was banned in some countries and even tagged with the first “mature” rating by the ESRB (Entertainment Software Rating Board). It was a bloodier more extreme version of Street Fighter and characterized a one-on-one, marital art versus martial art manifestation. Mortal Kombat and its concept was a huge hit among younger audiences. The stage was all but set for a “live” version of the game.

The momentum kept rolling and by March of 1993 (6 months before UFC 1), Best of the Best 2 hit theaters showcasing a fictitious no-holds-barred competition at “The Coliseum” with style vs style match ups where the only rule is, “there are no rules.” Sound familiar? Even the movie’s fighting arena was similar in shape to the UFC’s Cage only in pit format. While Best of the Best 2 was a box office flop, its theme obviously resonated with the UFC.

As Rorion Gracie and Art Davie continued to shop “War of the Worlds,” they were promptly turned down by every network willing to listen. While the heavyweights (HBO and Showtime) passed on the concept, WOW promotions finally struck a partnership with content provider Semaphore Entertainment Group (SEG), a pioneer in pay-per-view programming. SEG president Bob Meyrowitz signed off on the agreement, but it was Campbell McClaren and David Isaacs who brokered the deal so to speak. The two were extremely instrumental in the development of the early UFC model. Michael Abrahamson, a SEG employee, is credited with changing the WOW moniker and coining the title, “The Ultimate Fighting Championship.” The prep work was nearly complete.

Brazilian martial arts were about to explode in more ways than one, but Hollywood seemingly bet on the wrong horse. Only the Strong was released just three months before UFC 1, a movie based on the Brazilian martial art of Capoeira (the national pastime long before the Gracie family made their mark on society). Ironically its DVD tagline advertised it as, “The Ultimate Martial Art.” As the movie fizzled at the box office, the Ultimate Fighting Championship would catapult Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu to the top of the food chain and immortalize the Gracie clan on November 12, 1993 (UFC 1, later dubbed The Beginning). The Best of the Best 2 tagline, “there are no rules” was brought to life.

The UFC presented an opportunity to prove that Gracie Jiu-Jitsu was the world’s preeminent fighting art. The NHB concept, inspired by Rorion’s homeland, donned a “bloodsport” image that seemed to work within the confines of the motion picture and video gaming business, but proved far too brutal in the real world.

Children of the late 1980s and early 1990s were exposed to a lot of entertainment violence that celebrated the raw nature of martial arts. They would grow up to be the first target audience of modern MMA. The UFC brought an open tournament version of the “Gracie Challenge” to life in 1993, responding to the rapid change in public perception of that generation. Viola recalls, “The idea was played out over and over again by the entertainment industry. The UFC wasn’t a new idea pulled out of thin air; it was right there in front of everyone. Gracie had a point to prove, and just took the initiative. I appreciate his determination, his family honor.”

During the 1990s, the “reality” of what is or isn’t an effective martial art was reaching a boiling point. From Tae Bo infomercials to the comedy antics and stunts of Jackie Chan, the market was saturated with martial arts in one form or another; some tacky, some phony, some legitimate. Even future UFC President Dana White capitalized on the workout fads of the ‘90s, making his living teaching aerobics at local health clubs. For White, boxaerobics was a far cry from the Octagon, instead catering to stay-at-home mom types who more familiar with Richard Simmons than Royce Gracie. It is one of the sport’s great ironies that years later White, a boxing fan with little martial arts experience, would become the face of MMA. His rise to success is another story entirely. In any case, “Ultimate Fighting” had arrived, but mainstream popularity was still over a decade away.